Welcome to the New Blog

Why we left Medium, and how!

In 2016, elementary moved to a Medium publication to host our official blog. At the time, Medium was touted as a simple, clean, and reader-focused host for writers. They supported custom domains, a robust API, RSS, rich formatting, and great image embedding. We had been largely happy with the experience—as were our readers—but something changed in 2017.

The Decline of Medium

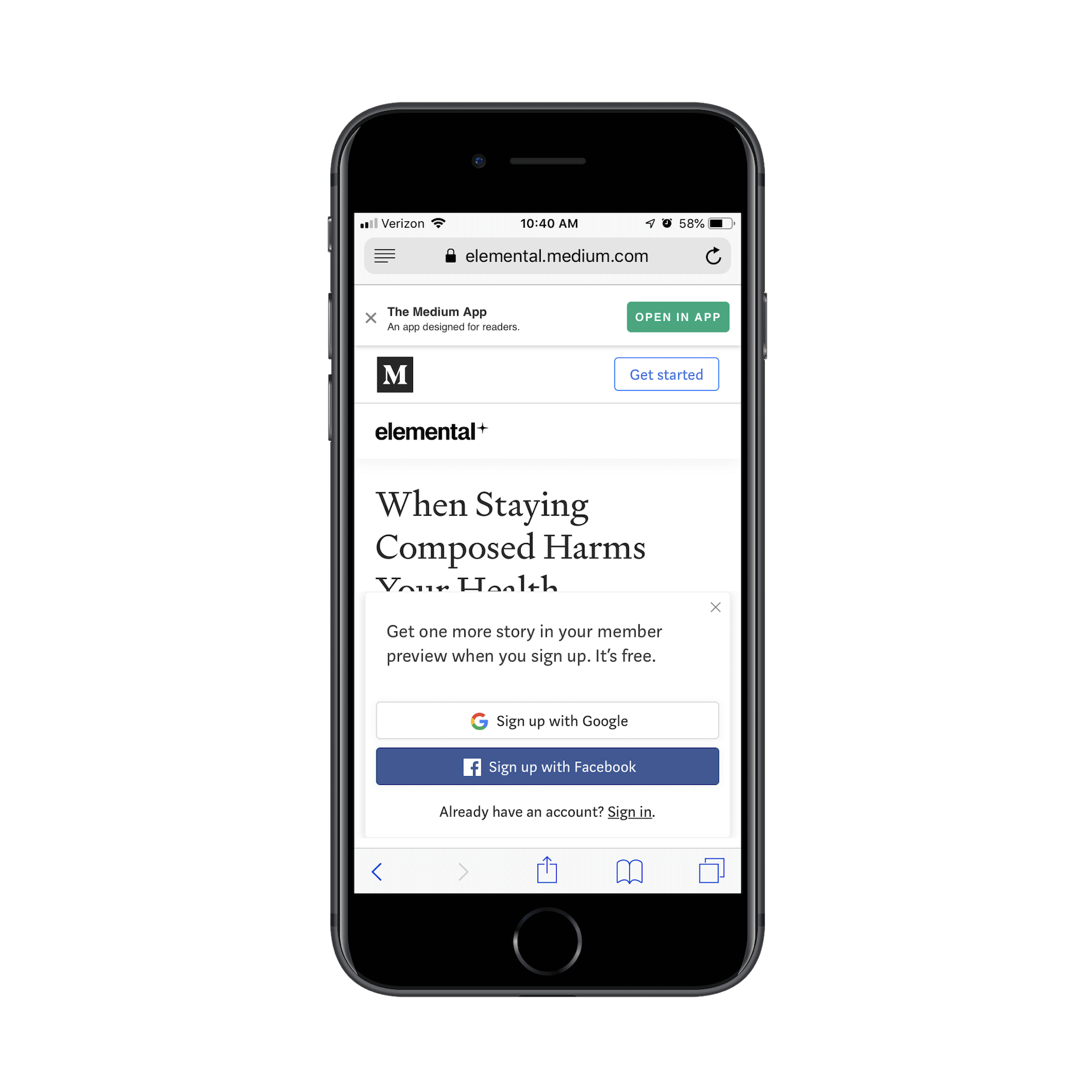

In their quest for financial sustainability, Medium started getting more aggressive toward readers. First, Medium removed the ability to create an account with an email address, instead requiring a third-party social networking platform. Then, readers who were not signed in—perhaps because they didn’t want yet-another-account tracking them across the Internet, or just because they were using a private browser—were shown modal pop-ups asking them to create an account.

Medium wants all readers to always be signed into an account so they can more easily track what individual readers are doing on their platform, serving them more relevant monetized stories. They also restrict how many monetized stories individuals can read before they upsell their subscription, which would be difficult without being tied to a user account.

The problem is that Medium has gotten overly aggressive with its upsells, calls to action, and pestering to pull readers away from the content they’re there to read. We’ve constantly gotten comments on Reddit, Twitter, and other social media asking us to move away from Medium due to these issues—and those pleas have increased substantially over time.

Screenshot of Medium’s reader-hostile UI from Webdesigner Depot

Medium has also gotten aggressive toward authors and publications. With their new monetized platform in tow, they started defaulting authors’ stories to be behind their paywall, with a tiny checkbox to opt out when publishing. Remember, this paywall actively reduces the potential readership of stories, as it restricts it to paying members. They also revoked API support, preventing publishing to Medium from other platforms. They removed custom domain support that had attracted several big-name publications in the first place, meaning all posts from future publications must be hosted at the branded Medium.com—putting the Medium branding more in competition with publications’ branding. They even served a heavy blow to their own partner publications by abruptly canceling their membership programs with little notice.

The authorship experience itself is also lacking in a number of ways: Medium arbitrarily blocks lesser-known browsers like Epiphany from using the editing tools based on user agent sniffing instead of checking supported features; image handling has been broken in Firefox for years without any response from the support team (to whom we also reached out privately); and formatting for posts seemingly randomly breaks based on global CSS changes on the site.

For a completely independent and privacy-focused company like elementary, it didn’t make sense to deal with this: we don’t need the social exposure across Medium (most people are coming from social media anyway), and we don’t care for our blog platform to track our readers while they catch up on official information. We would also prefer to use our own tools when publishing, and not be forced to install another browser just to write an update for our audience.

While we understand and empathize with the struggles of ethical monetization—and applaud Medium for refusing to monetize via intrusive ads and trackers—the direct result of their monetization model and product management has been a worse experience for our readers and authors.

Finding a New Home

We explored several options when looking for a new home for the blog. First, we checked out Write.as since we’d had some experience with the platform, and the developers are really great folks. Write.as excels as a way to painlessly publish thoughts to the Internet—anonymously or otherwise. If you’re an individual looking for a clean, reader-friendly Medium-like experience, Write.as is a perfect fit. However, it was lacking in some of the features we depend on, like multi-author blogs and collaborative authorship (i.e. having fellow team members review, privately comment on, and make suggestions to posts before they’re public).

We also looked at several traditional blogging platforms: WordPress, Ghost, etc. While these may have worked, we weren’t enthused about spinning up yet-another complex dynamic web server, or paying someone else to do it for us—especially when they felt like overkill in the first place.

We’ve used static Jekyll-powered sites, hosted via GitHub pages before: our AppCenter site is exactly that. I also have extensive experience with Jekyll, having done a lot of personal, professional, and freelance work in that space. So, I set out to investigate using Jekyll for the elementary blog.

Settling in with Jekyll

After a few days of spinning up a simply-themed Jekyll site on a private repo, I was convinced it was the way to go. It ticked all the boxes for us:

- Fast. Since it’s a static site, there’s no waiting around for pages to load and render on a server. They’re served as-is directly off a fast, global CDN.

- Total control. Since we are writing the entirety of the HTML, CSS, and JS, it means we can decide exactly what the blog is, looks like, etc.

- Privacy-first. Because we have total control and are leaning on the static nature of Jekyll, it means we can be fanatical about privacy: no external JavaScript, no analytics, no social tracking scripts, etc. Just what matters: the content.

The real selling point for us, however, was the authoring workflow. Since the code for the blog is hosted on GitHub, we can lean into our heavy knowledge and usage of the platform at the center of our normal workflow and apply it to the blog. If anyone in the org wants to write something on the blog, they just write it in Markdown and submit a pull request. The appropriate team can review that PR—just like all code PRs—and approve it before it is merged. Even better: anyone in the org can comment on, make suggestions to, and collaborate on the post using the GitHub UI. We even have CI running on the blog to make sure changes don’t break the build, and we can add HTML and CSS linters to that process pretty easily. It’s an awesome collaborative workflow that we already know, but for the blog.

Modern Features

Just because it’s a simple static blog doesn’t mean we don’t support all the modern features you’d expect:

- RSS feed for all the subscribing and cross-posting you could desire.

- Completely responsive design from the start.

- Great typography for long-form reading with sane line-lengths, pull quotes, etc.

- Dark style support from day zero (if your OS and browser support it).

- Rich image embedding with side-by-side layouts, zooming in, and full-bleed support.

- Sharing to social media without the privacy-invasiveness that usually comes with it.

One thing we’ve actively chosen not to implement or support is some sort of commenting system: while we could embed something like Disqus or another third-party commenting platform, it is just another place for people to worry about an account, for us to moderate, to track users, and to slow down the blog. Instead, we link to official posts that we’ve made about the story on social media, and offer up social sharing options (including a bare permalink) so readers can discuss it with us or on their platform of choice.

How It’s Made

So, how is the new elementary Blog actually put together? Let’s get web-dev nerdy.

Jekyll Basics

It’s pretty simple: first, we’re using the open source Jekyll project to generate a static site. Posts go into the _posts folder in the repository. These are Markdown files with a small amount of metadata up front like who wrote it and what image should be featured. That post is rendered by the _layouts/post.html template, which just sets up the header, wraps the content in an <article> tag, and pulls in a handful of _includes which help render reusable components like the author byline, the license, social links, and the “Up Next” posts.

We’re also using a handful of open source plugins to Jekyll for common tasks like generating an RSS feed, paginating the homepage, and generating a sitemap. We’re slightly restricted with what we can use since GitHub Pages generates the site using a --safe environment, but if we wanted to add more plugins, we could lean on CI to actually build and deploy the site. For now, though, the built-in GitHub Pages build and deploy works well.

No Tracking, Remote JS, or External CSS

One major constraint I set when starting the new blog was that we should avoid as many forms of tracking as possible. This sounds easy, but it turns out that modern web development practices heavily push you towards including external scripts, tags, etc. for simple functionality.

The obvious example is Google Analytics; while we do use this on our main site to track the number of downloads on the homepage (and are actively seeking an alternative method), there’s no compelling reason to include it here. It seems almost unfathomable to not include Google Analytics on a modern website, but we get enough sense of “engagement” via social media and press coverage to know what our users and readers find interesting. And since our goal for the blog is to spread genuinely useful information about elementary OS, we’re not incentivized to tailor our content to what gets the most clicks or attracts the “right kind” of readers.

A less obvious form of potential tracking is via common JavaScript libraries or CSS files that you’re encouraged to use by linking to a remote CDN. While that’s extremely convenient and has some caching benefits—if many sites use them, users are less likely to have to download them each time—it also opens the door to tracking: each time a reader visits our site, their browser is pinging that remote server to get the resource or see if it has changed. While we may decide to trust the companies that host those assets today, the reality is that web services pivot and may find those potential trackers too attractive of a market to pass up in the future.

We’ve also found that a clean, tailored blog doesn’t actually need any JavaScript to function (a near-blasphemous concept on the modern web!), and any tiny amounts of progressively-enhancing JS we may want can be included on the page where needed. For CSS, we use Sass to make it easier to write (and more organized across multiple component files), then the preprocessor compiles it all into one minified file.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

// Makes figure images focusable for zooming

let figureImages = document.querySelectorAll ("figure img");

figureImages.forEach (function (figureImage) {

figureImage.setAttribute ("tabindex", -1);

document.addEventListener ('mousedown', event => {

if (document.activeElement === figureImage) {

// Prevent it from triggering on focusIn

setTimeout (function () {

document.activeElement.blur ();

}, 100);

}

});

});

Closely related, but more nefarious, are the pervasive trackers disguised as convenient ways to share web pages on social media. Companies like Facebook and Twitter encourage web developers to pepper these “share buttons” across their sites, and it allows the services to directly track users and their activity across the entire Internet—whether logged into the social media service or not. In reality, these services also support sharing a URL via a normal link, which is what we use on the site to avoid loading any code from their remote servers.

Another great benefit: the site loads crazy fast because it’s not hitting and pulling down all kinds of external scripts and CSS.

Design & Styling

If you’ve read our stories on Medium, you might notice that the new blog feels fairly Medium-like in its styling. That’s not a mistake; our approach for styling has been to ease the transition from Medium while slowly moving to a more elementary-like style over time. This gives us a good typographical starting point, and helps our backlog of existing posts feel at home in the new design.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

:root {

--ui-font: "Open Sans", "Noto Sans", "Roboto", "Droid Sans", sans-serif;

--copy-font: "Noto Serif", "Droid Serif", serif;

--heading-font: Raleway, var(--ui-font);

}

html {

font-family: var(--copy-font);

…

}

h1,

h2,

h3,

h4,

h5,

h6 {

font-family: var(--heading-font);

…

}

.byline {

font-family: var(--ui-font);

…

}

One choice we made in the design was around the typefaces used: we decided to not include any fonts in the site itself, but to use a simple open font stack with native fallbacks. Platforms include high-quality typefaces these days, so using extra bandwidth to load in our own branded versions for a little bit of brand consistency just doesn’t seem worth it. If you are on elementary OS or have our default fonts installed, it’ll feel right at home—but otherwise, we use the OS’s default serif and sans-serif fonts.

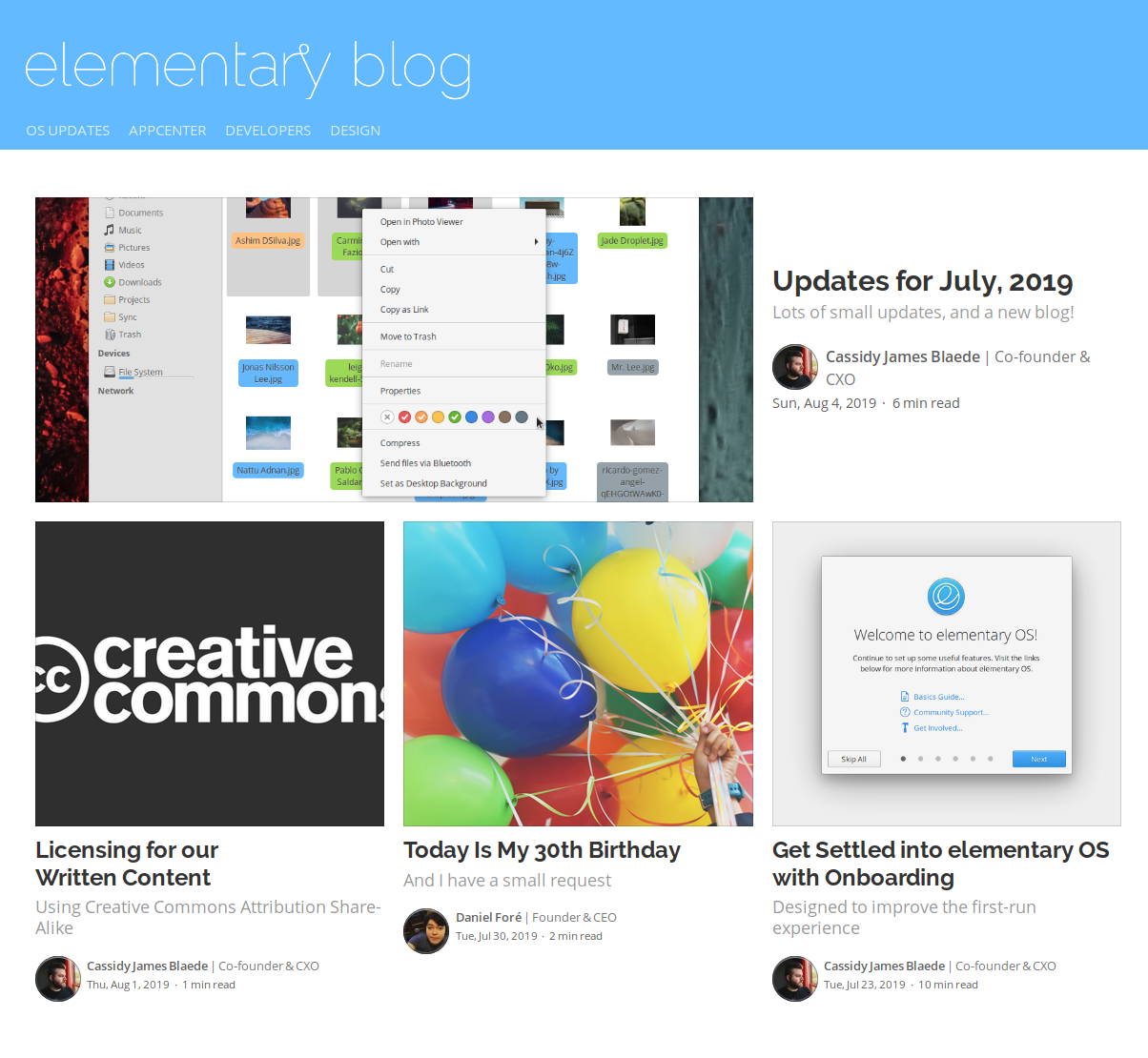

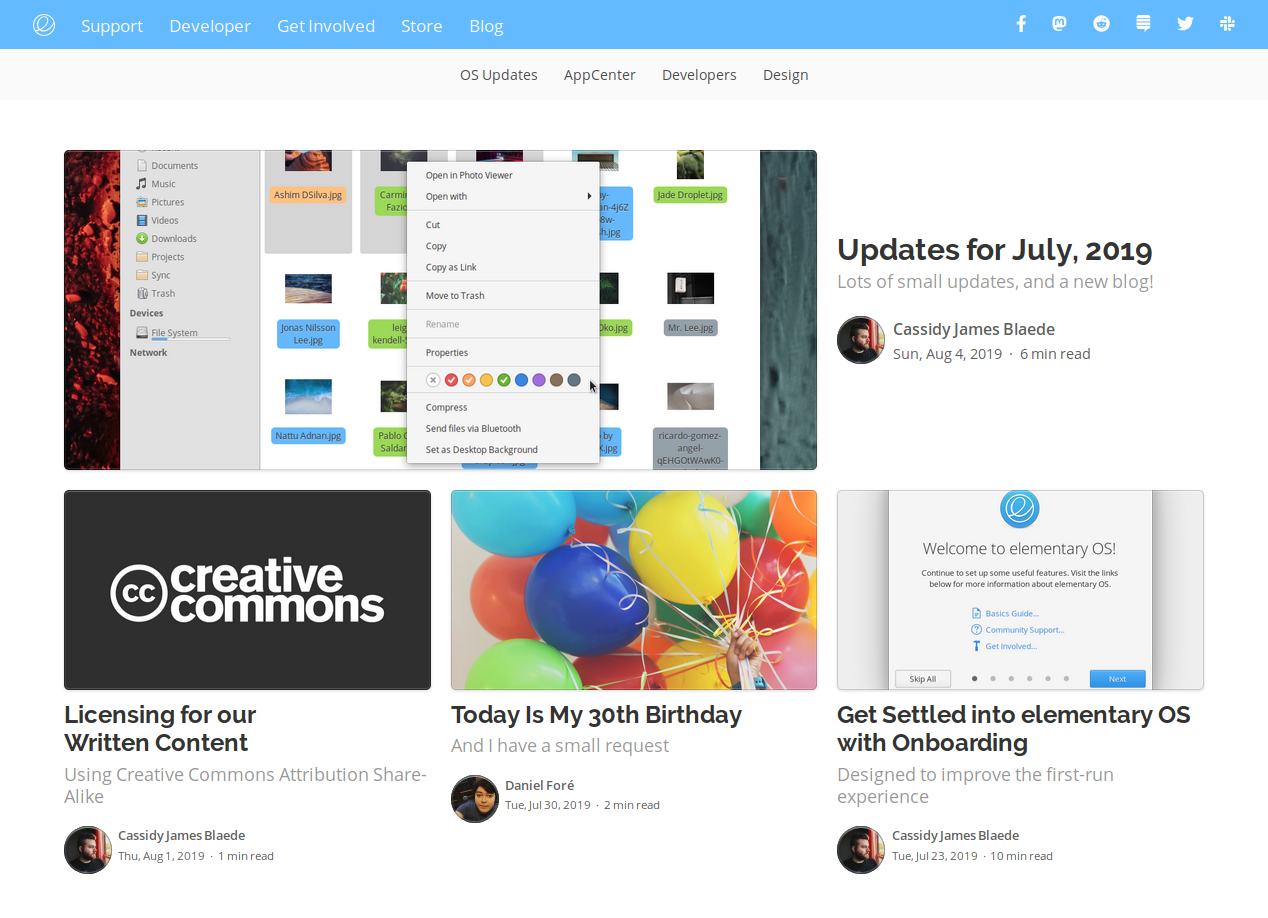

Left: Initial Medium-like homepage | Right: Newer, more elementary-style homepage

For the homepage, we started with a simple list of articles. To make it more visually interesting, we added a Medium-like grid of featured articles. Over time, we’ve tweaked this styling to feel more elementary-styled with subtle borders and shadows to make the images stand out. Similarly, with the author byline we’re using the same avatar style we use in elementary OS. For code blocks, we’re using the same excellent Solarized color scheme as used in our Code app.

Over all, the design has been and will continue to be iterative. We may add or tweak styling as we want to do new things. But we hope it’s a legible and familiar design both for former readers of our Medium publication and users of elementary OS itself.

Dark Style

One exciting area we could experiment with was supporting a dark style preference on the blog from day one. As I’ve written before, practically all major platforms and browsers are adopting a user-set dark style preference; we’d be remiss to not build a new site with that in mind.

We’re using CSS variables and the prefers-color-scheme media query to swap out colors when the browser requests a dark style. This means we can write our CSS more semantically, using rules like color: var(--fg-color) instead of hardcoding colors throughout the site. It also means we can style elements like code blocks with a light or dark syntax theme depending on the browser’s preference. While this isn’t (yet) supported natively on elementary OS, it should make reading the blog on other OSes like Android, iOS, Chrome OS, macOS, and Windows more consistent.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

:root {

--bg-color: white;

--fg-color: var(--black-500);

--accent-color: var(--blueberry-700);

--header-color: var(--blueberry-300);

--secondary-bg-color: var(--silver-100);

--secondary-fg-color: var(--black-300);

@media (prefers-color-scheme: dark) {

--bg-color: var(--black-500);

--fg-color: var(--silver-300);

--accent-color: var(--blueberry-100);

--header-color: var(--slate-500);

--secondary-bg-color: var(--black-300);

--secondary-fg-color: var(--silver-300);

}

}

We’re also experimenting with and learning a lot about the process of designing for light and dark styles at the same time, which may translate back to improvements in elementary OS.

No AMP

Right after we first deployed the new blog, Google alerted us (since it’s on a verified domain) that our new site didn’t support their AMP framework, and consequently could be deprioritized in search rankings. When testing if our site could be converted to support AMP we found that we’d need to add non-standard tags and scripts to our site, couldn’t use the tiny amount of progressively-enhancing JS we prefer, and would need to create duplicate AMP-version URLs of all of our pages. This is despite our site ranking 100/100 on Google’s own PageSpeed tool, for both mobile and desktop.

We feel that AMP is perhaps an acceptable technology that may solve problems for large, slow sites, but Google is unacceptably pushing it on all websites—and unfairly deprioritizing sites that don’t adopt their technology. Instead, we believe in web standards and the open web, and will continue to publish stories on a crazy-fast performing static blog without resorting to non-standard technologies.

Backfilling Existing Content

One of the most tedious parts of moving to our new blog has been trying to bring over all of our content from the Medium publication. While some tools exist to convert individual Medium stories or an author’s personal Medium archive into Markdown files, these didn’t always work perfectly and lost tags, image formatting, and other individually small but overall significant nuances. We tried exporting and procssing an archive of each author’s posts, but that meant wading through their personal stories as well. Medium did provide us with an HTML export of the entire publication (after we contacted their support team), but even processing that was a huge undertaking.

I spent a long time porting over important stories, but we still have a long way to go. Thankfully, Austin Delamar contacted us and helped port many of the stories over to drafts that we can hand-clean and publish as we get to it.

Unfortunately, because Medium shut down custom domain support, we have no way of properly redirecting the old stories on Medium to their new home on our blog—another reason to own your content and host it on a domain under your control!

Open Sourcing

Currently, our blog repository is private on GitHub; we need to be able to stage important announcements without them being public from the start. We’re still working out the best way to split the repository up so that the source is available for everyone while upcoming posts are private. Our main requirements are:

- The site layout itself is open since that’s the interesting part for other web developers.

- Upcoming posts are private since we need to collaborate on upcoming announcements, but wait to publicize them until they’re ready.

Ideally:

- Published content is open so that we can crowdsource edits, make translations easier, etc.

- We can schedule upcoming posts, which will probably require some CI magic.

If you have ideas and/or want to help, hit us up on social media!

Thank You

Thanks to all of our supporters, backers, and customers! Your contributions make elementary possible. If you’d like to help build and improve elementary OS, don’t hesitate to Get Involved.

We’re accepting limited sponsors for the elementary Blog. View our public analytics and learn more if you are interested.