Cassidy on GNOME, Themes, and More

The Linux Experiment interviews Cassidy for a video

Nick: GNOME, much like elementary OS, seems to want to put more effort into becoming a more stable and reliable platform for application developers. This has led to the creation of LibAdwaita, which regroups all GNOME-HIG related elements into a single lib that developers can target. elementary OS uses GTK, how does that move impact elementary?

Cassidy: This is a great move from our perspective, and is actually a solution we’ve been asking for for some time; we use GTK, but we don’t always use the same UI patterns or styling as GNOME. So in the past GTK may have forced GNOME-style dialogs or layouts that we had to work around, which we should see less of. By adding these GNOME-specific widgets and utilities to LibAdwaita rather than GTK, it keeps GTK itself more neutral and more flexible for desktops like elementary OS.

At the same time, there are some intriguing bits of LibAdwaita—especially around multi-touch gestures and animation—coming from its history as LibHandy, which we’re using heavily in elementary OS today. So I could see us using LibAdwaita in future elementary software, and because we’re in constant collaboration with GNOME contributors, that won’t be an issue for us; we will be able to use the bits that make sense while basically ignoring GNOME specific design bits.

All together, LibAdwaita is making it easier to make high quality GTK and GNOME apps without having to reinvent common patterns which is a boon to GNOME, elementary OS, and any desktop using GNOME or GTK.

Nick: Is theming the desktop important for a distribution? Is it just an aesthetic or a branding issue? Are there other advantages?

Cassidy: So before I really answer this, I think we need to clearly distinguish the parties involved in these discussions and decisions.

First, you have the people making the GNOME desktop. GNOME is less like a traditional top-down software company and really more like a collective of people with overlapping ideals but often very different opinions! This is great for a diversity of thought but sometimes can be frustrating because there is not a singular person or vision you can point to for the ultimate direction of GNOME; you have to look at the direction as a whole, and understand that there are many, many people who are generally steering GNOME in the direction it is going.

Group photo from the GNOME User and Developer Conference 2019. Contributors pictured include individuals from CodeThink, Collabora, elementary, Endless, Igalia, Purism, Red Hat, System76, Ubuntu, and more.

Cassidy: Within that collective of people, you have who I tend to call the “progressive app developers” who are longing for a better experience that has more modern patterns, easier ways to build apps, and modern features that many have gotten used to e.g. on popular mobile OSes. These folks are generally the ones behind the “Please Don’t Theme Our Apps” initiative, and include folks working on pushing GNOME tech and design forward by working within the design team and on tools like LibHandy and LibAdwaita.

Then you have desktops or distros using GNOME downstream more as building blocks to make their own experiences; this probably includes Ubuntu, Pop!_OS, and many others. These projects have their own goals and don’t always work directly within the GNOME community to help steer GNOME, but may still contribute bits upstream like bug fixes and performance improvements. In my mind, the distinguishing characteristic of this group is that they use GNOME to build their own experience, but are also leaning heavily on the GNOME ecosystem rather than building their own, separate ecosystem.

Then separately, you have desktops like Pantheon on elementary OS where we are using some GNOME technologies or components under the hood, but building our own desktop environment, experience, and ecosystem in parallel. We often work within upstream projects, but aren’t shipping GNOME, nor are we directly steering GNOME (other than occasionally via design influence 😉). We ensure compatibility between our desktops and ecosystems by heavily leaning on FreeDesktop standards and being in constant communication and collaboration with projects like GNOME, KDE, and any shared upstream projects.

Last but not least, you have the actual users of the software whose opinions and wants are as diverse as the people within the GNOME community itself.

Each of these groups probably has a different outlook on “theming,” but I can answer from the perspective of the progressive GNOME folks and elementary-like ecosystems, plus users (based on years of research and user studies).

For both the progressive GNOME folks and elementary, we largely see traditional theming as we know it on Linux desktops as a legacy implementation that is unique to “desktop Linux” for the worse. It is unlike any mainstream platform and makes it difficult for app developers to design and develop innovative, modern experiences. This is why elementary OS and GNOME 3 have never officially supported arbitrary theming via switching out the system stylesheet. There is absolutely an aesthetic and branding aspect (it’s nice for screenshots of elementary OS to be recognizable as elementary OS, for example), but more important is avoiding breakage for both app developers and end users. With elementary OS, for example, we often see people who switch out their system stylesheet get upset when there is poor contrast, broken widgets, or features (like the dark style or accent color preferences) that no longer work for them. We also see third-party apps that are doing interesting custom widgets—some of the most innovative and unique apps!—completely break because a third-party stylesheet doesn’t support the variables or style classes they depend on to make it easier to make their app.

However, for users, there are three main aspects to “theming,” and this is backed up by my years-long research and studies like the recent Custom Styles, Dark Modes, and Night Light user interface study: first, aesthetics—or as I like to call it, “making it your own.” This is the same reason we have wallpapers on every modern OS (and look at early versions of iOS to see the opposite end of this line of thinking). People want to make their computer feel like theirs, just like they might want to decorate their physical desk with their own style to make it more pleasing for them. The second major aspect is accessibility which encompasses contrast and light/dark style preferences; some people have an easier time using their computer if it temporarily or permanently looks different than the defaults. Lastly, there’s the “familiarity” aspect which often overlaps with the previous two, but can also include things like a theme to make the OS look more like Windows or macOS.

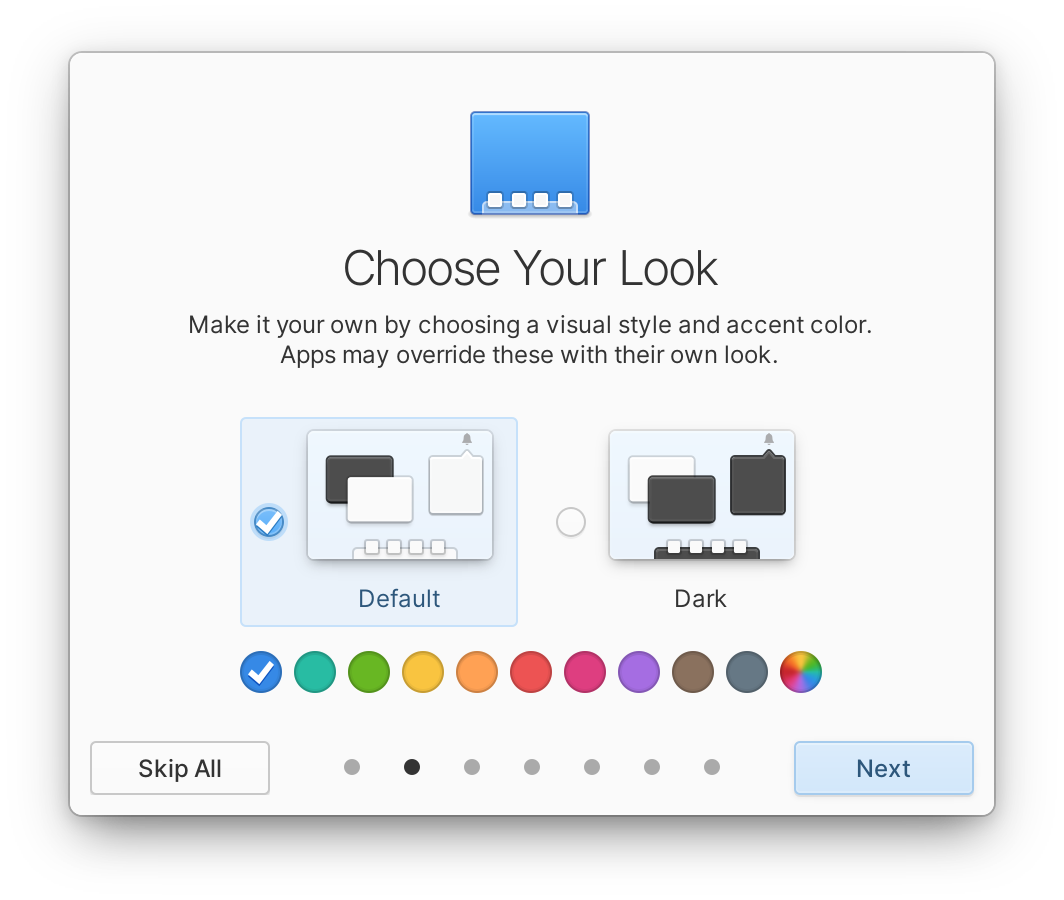

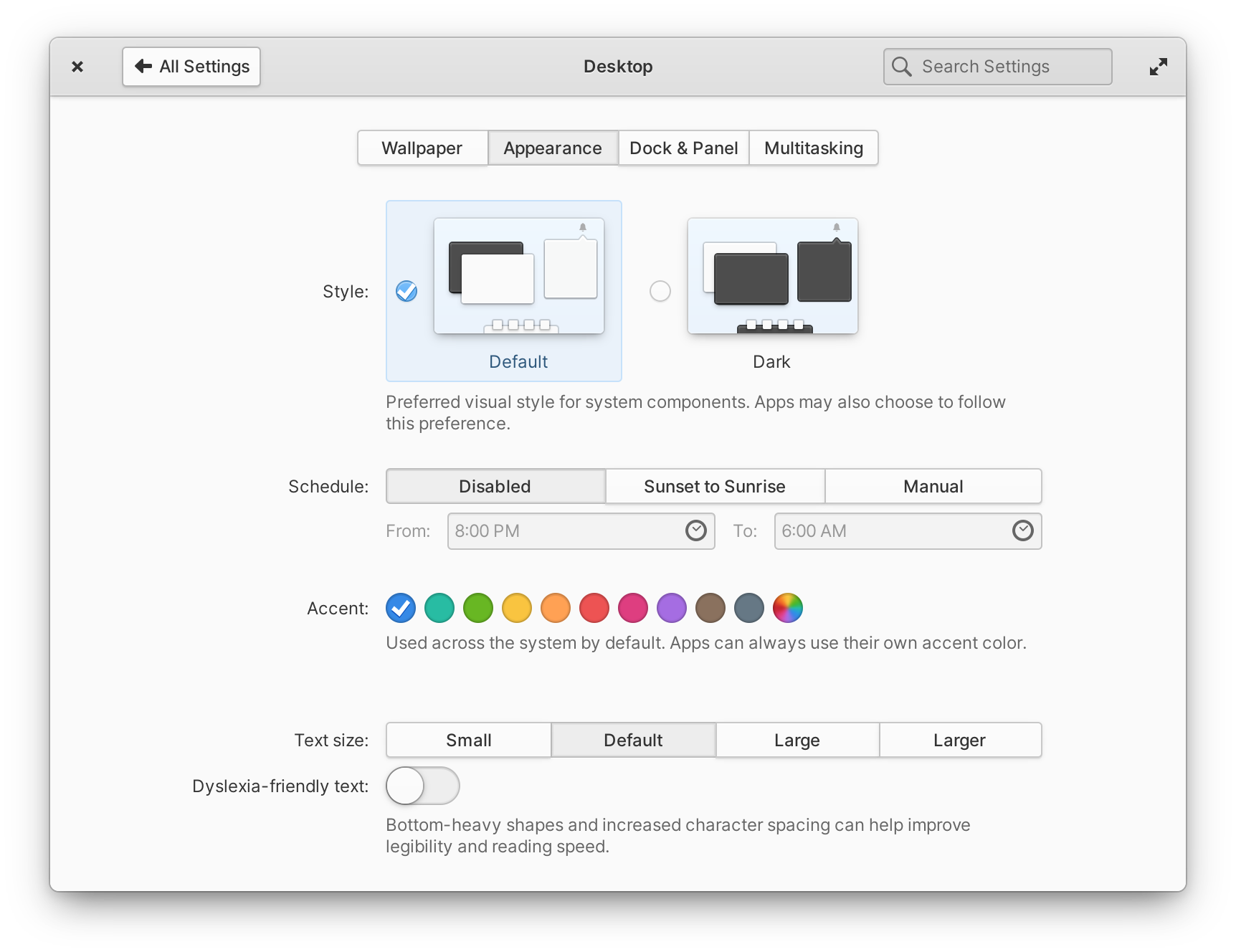

Cassidy: From the elementary perspective—and seemingly the progressive GNOME perspective with recent developments, we’re tackling the first two aspects differently than just arbitrary themes; we’ve added a dark style preference and app API to address the aesthetic and accessibility needs for a dark interface while ensuring it’s well supported by apps. We’ve even had success moving this under the FreeDesktop banner via a Portal API and now future GNOME versions will be shipping a compatible API as well (which gives me hope for third-party apps like Firefox and Chrome supporting it on Linux, too).

We’ve also added ten new accent colors to elementary OS and a refreshed stylesheet that uses them throughout the OS in places like highlighted text, selected options, suggested actions, focus glows, and even accented text like in the Date & Time indicator. As a result, you can keep the default stylesheet and still make elementary OS feel very personalized—while also ensuring it passes accessibility standards for contrast, and without breaking third-party apps. In fact, these new features are made possible because of the default stylesheet. So for us, we’re happy to talk to users to discover how and why they are leaning on theming, and address those directly in the system stylesheet. Of course with open source software people will always be able to go and change how it looks and works, but we’re focused on making the default experience address the majority of those cases while also avoiding breakage.

Left: Dark style and accent colors in the Welcome screen | Right: System Settings → Desktop → Appearance

Cassidy: The last perspective I can touch on is the downstream GNOME-based distro perspective, but is one I’m less qualified to answer (because I don’t share the opinions). However, I can share my understanding from interacting with those folks and having previously worked at System76 on Pop!_OS. From my understanding, the biggest reason they want GNOME and GTK to officially support arbitrary theming is for their own vendor differentiation; Pop!_OS should look different from Zorin OS, should look different from Ubuntu, etc. They see the aesthetic of the software as part of their brand identity and one potential reason a user or customer might choose them over something else.

I always draw parallels with the Android ecosystem here, though, because I think we’re seeing the same thing play out. Early versions of Android were heavily skinned inside and out by OEMs differentiating their offerings. In some cases, it was because stock Android was subjectively ugly or incomplete, as well. But as Android as an ecosystem grew, OEMs (often via their agreements with Google) stopped modifying the toolkit and core styling of Android itself so it interfered less with third-party apps, but still differentiated their offerings with their first-party apps (often forks of the AOSP apps) and their “System UI” changes (much like changes to GNOME Shell on a GNOME-based OS). As a result, they now have a diverse ecosystem of devices with different experiences, and some people greatly prefer one brand over another for their unique approach to the experience. But for users, an app that works on one phone will work the same way as an app on a phone from a competing company. These OEMs are using Android to create a device and experience, but are all participating in the Google Play/Android ecosystem. But then you also have companies like Amazon who are using the Android platform to build their own separate Kindle/Fire ecosystem, and not participating in the larger ecosystem. Both approaches are valid and have benefits, but you kind of have to pick one or the other. And then on top of either ecosystem, you end up with users who root and install custom modules to customize how the OS looks and works themselves.

Wow, that’s quite an answer. To summarize my thoughts on this original question, I personally think theming at a user level will always have a place for the tinkerers and experimenters; I even got my start in OS design by hacking on Windows 98 and Windows XP to swap out custom styles! But I think a successful modern ecosystem needs to make some guarantees to users and app developers about how the platform looks and works, and the current state of swapping out entire stylesheets from under apps is not sustainable. This is why platforms like GNOME and elementary OS are adding well-defined features like dark style APIs and accent colors, and why there is interest within the GNOME community in developing a well-defined theming API. I think that’s the best way forward for all parties.

Nick: elementary OS already has a similar “platform library”, with Granite. Will Granite be inter-operable with LibAdwaita, will both libraries be able to benefit from each other’s work, or will they just be separate?

Cassidy: I don’t expect to see much change in how we approach Granite; it exists primarily as a way to abstract common patterns in real world use in elementary apps into reusable widgets and utilities. If LibAdwaita implements something similar to an existing pattern but it’s better in some way, we could switch to that and deprecate our own Granite implementation, as we’ve done in the past when things have been added to GTK or LibHandy. Granite and LibHandy are currently perfectly inter-operable, and we expect the same to be true with LibAdwaita, again, because we’re in constant collaboration with the folks working on it.

Nick: Have you had talks about this with GNOME developers, to see if development efforts can be combined?

Cassidy: Yes, we’re in constant communication with folks working on GNOME and are always finding ways we can work together. And GNOME contributors are excellent about reaching out and getting our opinions on things when they’re being worked on as well, like with the new LibAdwaita tabs or the new dark style Portal API. Even though elementary OS is downstream of many GNOME components, I do feel like we’re often a proving ground of new widgets, designs, or APIs that then make their way back up into GNOME while also handling more use cases—and when that happens, we’re happy to deprecate our implementation. I think this approach is more productive overall than if we were to solely work within GNOME to implement our ideas, as we often update apps and widgets faster than would be possible in GNOME, or ship a certain pattern that GNOME designers aren’t convinced of just yet as a way to prove it in action.

Nick: Developers will have to decide between the GNOME platform, the elementary platform, or the KDE platform. Could that make the Linux app development situation more complicated than it already is?

Cassidy: We already see this today, and LibAdwaita doesn’t change that. A GNOME app doesn’t look at home on elementary OS because we have different Human Interface Guidelines and conventions, and that has always been the case. Just like a KDE app doesn’t look at home on GNOME, and it’s not realistic to expect it to.

But this is also not unexpected from the status quo; we have popular apps like Spotify, Discord, Chrome, Steam, etc. that don’t really feel native in any desktop environment, but it’s important to users that they can use these apps regardless of their preferred platform. With cross-desktop standards that GNOME, elementary, KDE, and others are working on together, it means we can have our own implementations while ensuring compatibility. It’s the whole reason you can even install a KDE app on GNOME or elementary OS and it correctly gets a launcher icon, is managed by the window manager, and can integrate with the desktop in places like the sound menu; we have FreeDesktop.org standards and efforts like Flatpak where we are all working together.

Of course from the elementary perspective we hope our platform is an attractive target for indie developers, and we work hard on our documentation, Human Interface Guidelines, platform features, and app monetization model to ensure that. At the same time, an app built for elementary OS and distributed on AppCenter is also trivially installable on any modern Linux-based OS thanks to our AppCenter for Everyone efforts, ultimately increasing the size and diversity of the “desktop Linux ecosystem” if you want to look at it that way. So I don’t see it as in conflict with GNOME; we have differing visions for our platforms, but work together when it benefits us all.

Nick: If app developers decide to force the use of Adwaita in their applications, could this lead to less consistency overall? With desktops made of apps themed by the distribution, apps built for elementary OS, apps built for GNOME, all with their own HIG, theme, and look and feel?

Cassidy: I think my answer here is partially covered in the above answer as well. But more specifically, I don’t believe surface-level consistency is a worthwhile ultimate goal; if I was shipping an Android app, I would design and write it using native Android patterns and tech. If I were shipping an iOS app, I would do so with native iOS tooling and patterns. I wouldn’t expect my Android app to look “consistent” on iOS, and vice versa. In the same way, I don’t expect a KDE or GNOME app to be “consistent” on elementary OS; even if it were using the same colors on the surface, the way those platforms look and work are just different.

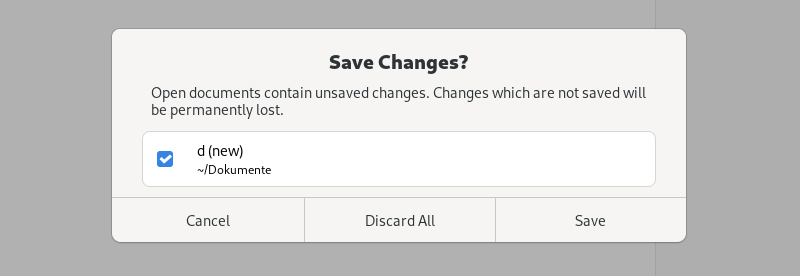

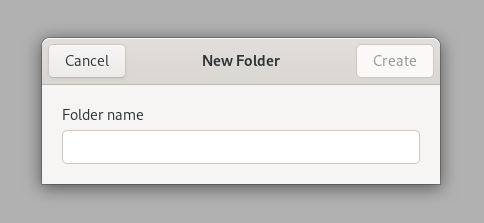

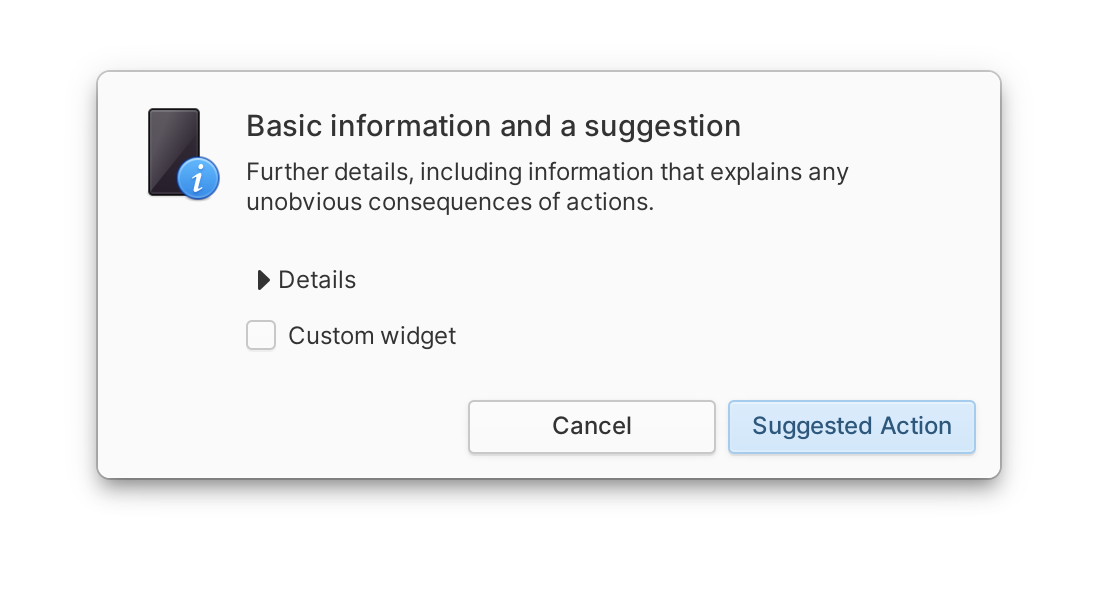

Left: GNOME Message Dialog | Right: GNOME Action Dialog | Below: elementary Dialog

Cassidy: As an example, dialogs in all three platforms look very different from one another, including where the suggested button is placed. Should apps adapt for every possible platform, or should they just use the conventions of the platform they were actually built for? And none of that is solved with theming, but requires code changes from the developer themselves.

However, it’s a pretty cool result of our collaboration and standards that you can use those apps on elementary OS, and that is worthwhile.

Nick: elementary OS has always been focused on the user experience. Could that move in favor of app developers result in a less coherent experience for users, with desktops made of apps themed by the distribution, apps built for elementary OS, apps built for GNOME, all with their own HIG, theme, and look and feel?

Cassidy: I think this is also pretty well covered earlier, but yes, it can and has resulted in a less consistent experience on a surface level. But that’s not new, and not solved by anything to do with theming; it’s a result of having different inter-operable platforms. The only way to solve this is to make “desktop Linux” a singular platform with a single set of Human Interface Guidelines and a single toolkit and a single stylesheet and a single desktop and… yeah, I don’t think we want that, either!

Thank You

Thanks to all of our supporters, backers, and customers! Your contributions make elementary possible. If you’d like to help build and improve elementary OS, don’t hesitate to Get Involved.

We’re accepting limited sponsors for the elementary Blog. View our public analytics and learn more if you are interested.