Building the Next Generation of Apps

Platform improvements and goals for Juno

For a little over 7 years now, elementary has set out to bring killer apps to Open Source desktops. During the Juno development cycle we’ve been working hard to deliver our vision of those apps, but not all of the work we’ve done is visible to the casual user. In this post, I’ll be talking about a bit of history surrounding how we put things together under the hood and what the new normal looks like for elementary apps. Strap on your dev helmets, and let’s get geeky.

Gen I

We delivered the very first version of elementary OS with our best shot at developing compelling Open Source apps. We had no standard language. Apps were written in Python, C#, C, Vala, anything. There was no code style guide. Our code was very messy and not very consistent. Gtk2 was a thing. And also drawing things by hand in Cairo. It was the “duct tape and bailing wire” era of elementary app development.

](https://cdn-images-1.medium.com/max/800/1*mSYq1zRGcnUw7QBam3Lyhg.png)

0.1 Jupiter, best viewed with this accompanying score

During our trip to the Ubuntu Developer Summit way back in 2011 after pitching some of our new apps to the Ubuntu Desktop Team, we sat down with Unity developer Jason Smith who delivered a hard truth to us: we weren’t a great code shop and we needed to change the way we worked.

Gen II

We made a lot of hard choices during the development of Luna and some of them cost us valuable contributors. The two biggest changes were standardizing on Vala and introducing code reviews.

Picking a standard language was really the gateway to raising our standards. This made it much easier for anyone working on one app to be able to easily contribute to another app and it allowed us to create a single code style guide that everyone could become familiar with. Later it would allow us to write comprehensive developer docs and give 3rd parties a clear path to delivering their apps to elementary OS users. We also chose a standard build system with CMake for similar reasons.

Introducing code reviews was a much more arduous task. Unlike modern tools like GitHub, our code hosting platform of yore, Launchpad, did not have any native concept of reviews. We started using a bot called Tarmac which was what developers at Canonical had begun using. It was slow and painful and some developers took it really personally that we wanted their code to be peer reviewed before it could land in the development trunk.

Starting in Luna, but throughout Freya and even into Loki, we strived for a pure Gtk3 desktop and I’m really proud to say that we finished our transition before many other projects had even begun theirs. We embraced and implemented HeaderBars across the board, even in places where GNOME hasn’t yet. Gtk3 also allowed us to create more complex, custom styles with CSS and introduce better typography into our apps with much finer grained control over font heights and weights.

We also introduced a new library called Granite to share common code across projects and extend the things we got from GTK. Many of the widgets we built would eventually be replaced by implementations in GTK itself including HeaderBars, Popovers, and more. While Granite continues to be improved and new functions and widgets are added, we’re also very excited when we can deprecate classes as GTK gains features.

Gen II was long and good and it brought a lot of great advancements to the way we built apps. It’s been a time of gradual change without too many major upsets since we made those hard choices in Luna. Time to shake things up.

Gen III

With the newest generation, we’ve made several large changes with the goal of making it much easier for new contributors to get involved and for old contributors to maintain mature code bases.

One of the biggest ones is fully embracing Reverse Domain Name Notation (RDNN). Because of our long history, new contributors might find that when they, for example, clone elementary/files the binary name of the project is pantheon-files, the .desktop is called org.pantheon.files, and settings are stored at net.launchpad.marlin. When all naming is RDNN based, new contributors can easily predict that the names of binaries, .desktops, GSettings paths, etc will always be, for example, io.elementary.files. This also guarantees that we don’t have file naming conflicts with packages from our upstreams like Debian or Ubuntu. You can read more about that in Cassidy’s previous article, “Cleaning Up App Codenames”.

We’re also pushing to have a consistent source tree directory structure with standard files like Application.vala in the src directory which contains the Application class (imagine that!), an expectation that you can find .desktops and appdata.xml in the data directory, etc. This makes it easier for developers working on multiple projects to quickly find common files across projects.

Gen III apps also make use of GResources for custom assets like icons, images, and CSS instead of installing files to the filesystem. This is important both for ensuring that these assets don’t cause packaging conflicts if installed to a system directory like the hicolor icon directory and for reducing IO errors and increasing performance.

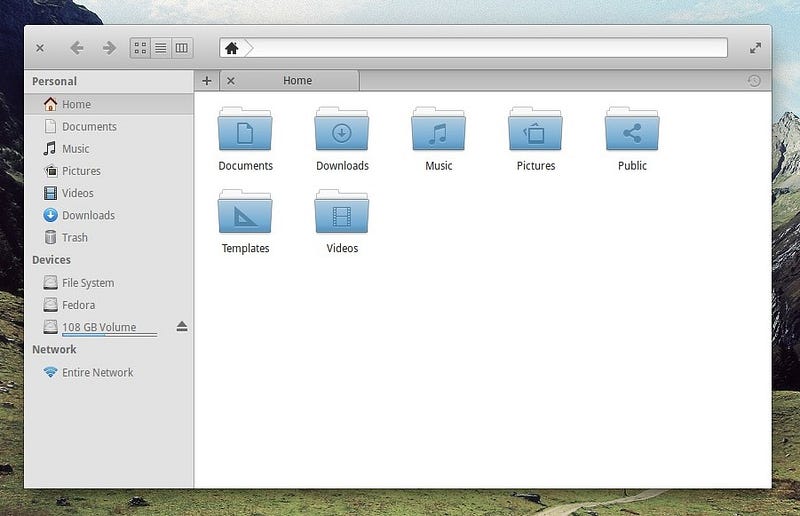

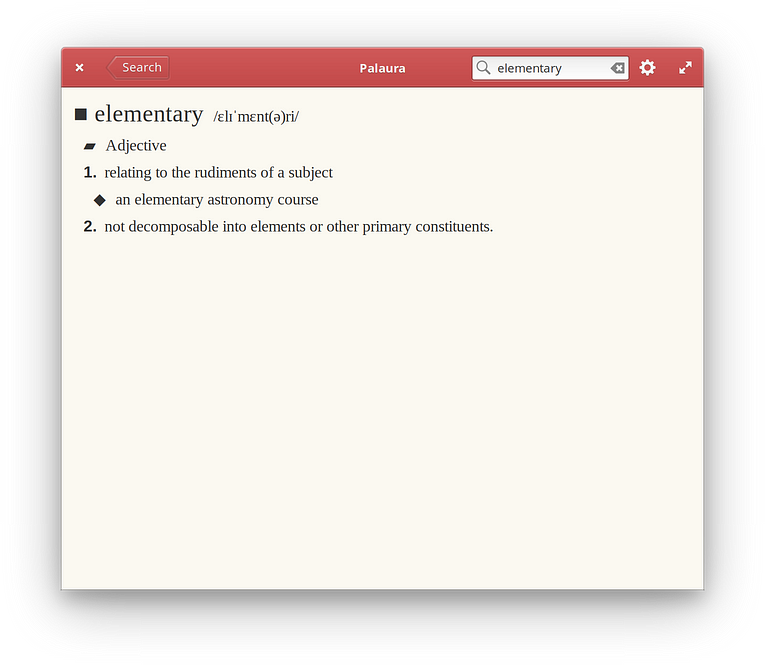

Left: Lingo, a Gen I app | Right: Palaura a Gen III app

You’ll also notice many Gen III apps making much more comprehensive use of Gtk.CSS to provide branding, including things like more stylized typefaces and colored HeaderBars. You can read more about some of the tools available to developers here in our most recent Developer Tips article.

We talked last year about embracing new metadata standards in the form of AppStream and ditching “About” dialogs. We’ll be continuing down this path and are currently investigating new standards like OARS which would allow new forms of Parental Controls and ensure that users have more control over the kind of content that is consumed on their devices.

We’ve also made a ton of progress with building all of our apps with Meson and have contributed patches upstream for better Vala support and localization tools. You can read more about that here.

Last, but not least, we’ve made much more comprehensive use of automated testing in the form of Travis CI on GitHub and Flightcheck, our testing solution for AppCenter Dashboard. Continuous testing in addition to code review helps us to keep code and metadata quality high and avoid introducing regressions. At the moment, we’re testing a continuous version of Flightcheck to make it easier for anyone to run the full suite of elementary-maintained tests with Travis. More on that soon.

We also hope to deliver more tools and better documentation throughout the Juno cycle, so stay tuned here to our blog for more info about how you too can deliver killer Open Source apps.

Thank You

Thanks to all of our supporters, backers, and customers! Your contributions make elementary possible. If you’d like to help build and improve elementary OS, don’t hesitate to Get Involved.

We’re accepting limited sponsors for the elementary Blog. View our public analytics and learn more if you are interested.