What is HiDPI

and Why Does it Matter?

I’m a web developer and UX architect formerly at Ubuntu computer manufacturer System76, and cofounder of elementary OS, an open source desktop operating system. I’ve worked with desktop, web, and hardware developers to implement HiDPI and have noticed many have a hard time understanding this complex topic because there’s not a whole lot of good information out there. This is my attempt at both introducing HiDPI and knocking down some common misconceptions I’ve heard.

HiDPI displays are becoming more and more popular on computers: Apple’s recent MacBook, MacBook Pro, and select iMac models sport them (billed as Retina, more on that in a bit); Microsoft’s Surface, Surface Book, and fancy new Surface Studio rock them; Dell, Lenovo, HP, and others offer them as options on laptops; LG, Dell, and Philips make HIDPI desktop displays; and System76 (my employer) just announced HiDPI on their flagship Oryx Pro and insanely powerful Bonobo WS laptops.

Update: More recently System76 has also expanded the HiDPI lineup to the 13” Galago Pro and the beastly Serval WS. And they have different resolutions! More on that in a bit.

Due to the general increase in price, graphics requirements, and power draw they’re not quite the default on computers yet, but we’re definitely moving in that direction. So, what’s the deal with HiDPI?

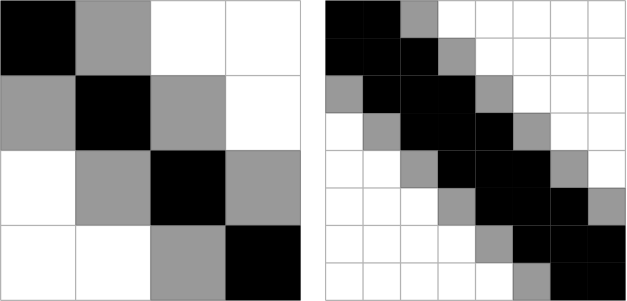

Pixel Doubling

At the heart of HiDPI is pixel doubling: drawing an image with twice as many physical pixels in each dimension than requested in virtual pixels.

For example, an icon or image might be 64 virtual pixels tall, but on a HiDPI display, it’s drawn with 128 physical pixels (effectively using four times the total square pixels — twice as many in each direction — but for simplicity sake is referred to as doubling or a 2× scale). This makes the icon twice as crisp in any angles or curves, or allows for twice as much detail in the photo.

1× vs 2× (HiDPI). With 4× as many pixels. HiDPI allows crisper shapes and better aliasing.

1× vs 2× (HiDPI). With 4× as many pixels. HiDPI allows crisper shapes and better aliasing.

For user interfaces, it means they look more like crisp, perfect shapes than a collection of pixels. For photos, it makes them look more like a printed photograph than a digital image. For text, it makes it look more like a physical magazine than a computer screen. For video, it allows for more detail and immersiveness as the screen fades away and becomes a window into the film.

Half Pixels are a Lie

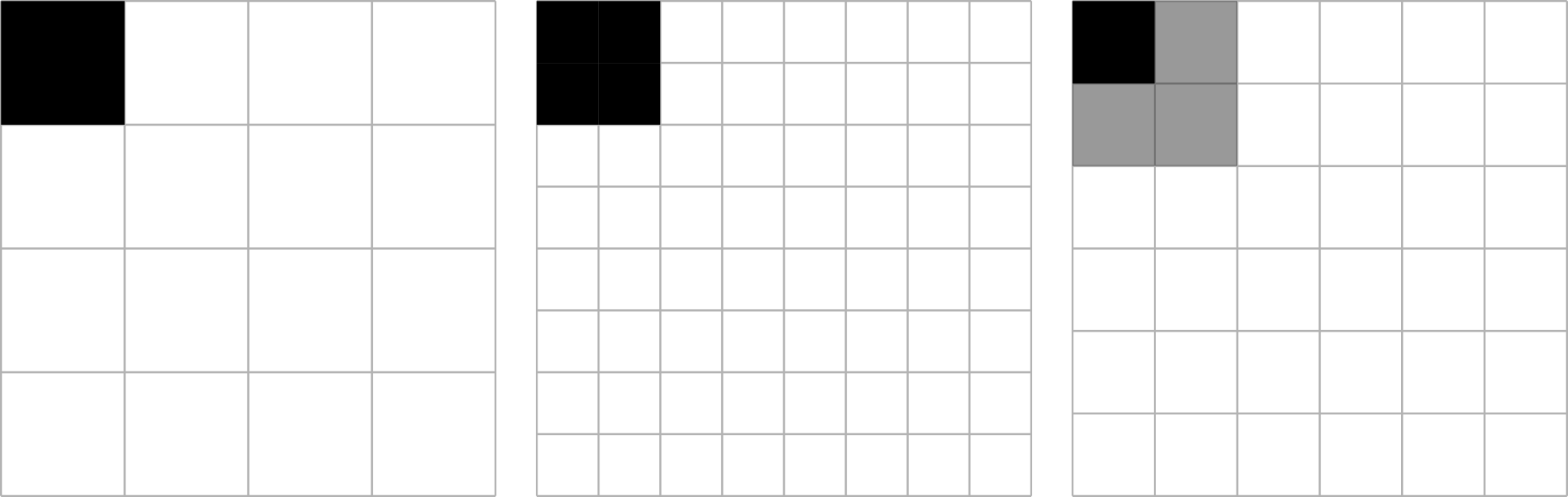

So, why pixel doubling and not just increasing the density on a 15” display from, say, 1080p to something like 2880×1620? To get you user interface at the same physical size* as on the 1080p display, you would have to scale it by 1.5×. That means a dot that is requested to be drawn at 1 virtual pixel now has to be drawn at 1.5 physical pixels.

Half pixels don’t exist, so the software would have to compensate with aliasing. Aliasing = blurring. So with a higher resolution display, you get a blurry UI. Fonts do have mechanisms to deal with this, so it’s not an issue there, but UI elements like icons and strokes around buttons will end up looking worse on a 1.5× display than a 1× display.

1×, 2×, and 1.5× scaling drawing a 1px dot. On 1× and 2×, the dots look identical. On 1.5×, software has to compensate and aliases, creating a fuzzy edge.

1×, 2×, and 1.5× scaling drawing a 1px dot. On 1× and 2×, the dots look identical. On 1.5×, software has to compensate and aliases, creating a fuzzy edge.

Some argue that the pixels are small enough that the aliasing/blurring isn’t immediately obvious. That is possible with some size/resolution combinations, but if that is the case, 1.5× is no better than 1× at that physical size, and you’re just wasting processing power and battery by pushing that many more pixels.

*Some (i.e. Linus Torvalds) think this is “insane” and want 4× resolution to equal 4× real estate, even when that would mean tiny, unreadable fonts and icons. They can have their opinions, but for most consumers that would make the device less usable. And for the handful of technical users who want that, they can work around this by manually setting the scaling factor anyway.

4K? Quad HD? 5K? UHD? Retina? HiDPI?

HiDPI is a great idea, but it’s a hard concept to explain to customers (and some manufacturers don’t even seem to get the benefits, see the next section). So the industry has come up with several different buzzwords in an effort to pitch it it customers, with varying success.

Retina

Arguably the most effective of these efforts comes from Apple with their Retina branding. They describe Retina as meaning so pixel-dense that the human retina can’t discern the individual pixels at a normal viewing distance. That’s accurate, but also a bit of marketing speak compared to how they use it in practice. For Apple, Retina seems to simply mean pixel-doubled.

When they announced their first Retina display, it had 4× the pixels (2× in each dimension) than the display it was replacing. This avoids the blurryness of using the same assets as 1× displays (they look the same on the new display, no better but no worse), and makes for easy math for designers/developers producing new assets.

Apple has stuck with this convention as far as I can tell on every Retina-branded display produced since; they’re all simply pixel-doubled from the previous display, and set to 2× scaling in software.

4K, Quad HD, 5K, and UHD

Technically, 4K, Quad HD, 5K, and UHD have nothing at all to do with pixel density and HiDPI. However, since they’re the terms used to sell projectors and TVs, computer manufacturers like to use them to upsell from the “lowly HD” displays they’re replacing.

Don’t pay much attention to these marketing terms; instead, look at the resolution and think if that amount of virtual real estate makes sense on that display. If it seems way higher, divide each dimension by two. If that resolution doesn’t make sense at that size, don’t buy because the manufacturer made a poor decision: out of the box, the device requires half or fractional pixels to be usable.

As a general guide: Quad HD or 1440p (2560×1440) is the same real estate as 720p, but at 2×; 4K (3840×2160) is like 1080p at 2×; 5K (5120×2880) is like 1440p at 2×; UHD is not consistent at all — divide the device’s resolution by two to get the real estate. Now combine that with the physical size: 1080p can make sense at native resolution on 14” to 24” displays, so 4K makes sense as the HiDPI versions of those display sizes. 1440p can make sense on 24” to 30” displays, so 5K makes sense as HiDPI at those sizes. On smaller displays (around 11” to 13”), something like 1600×900 might make sense for the native resolution, so HiDPI could be 3200×1800 (which is incedentally what Lenovo and Dell have done with some of their 13” HiDPI displays).

HiDPI

In the desktop Linux world (and it would seem in Windows land as well), the term HiDPI is being adopted as the manufacturer-independent version of pixel-doubling or “Retina.” Few manufacturers are actively using this term (System76 is!), but software developers tend to know and use it. I’d love to see it picked up as an industry standard term if used properly.

Some Manufacturers Make Poor Decisions

Higher resolution is not always better. In an effort to upsell from their lower-resolution displays, some manufacturers are jumping on the 4K bandwaggon without considering the physical size and how pixel doubling works.

On a 15” display, 1080p (1920×1080) at 1× scaling produces a great usable amount of real estate without the fonts and icons being too small. 1080p pixel doubled is 4K (3840×2160), so that makes sense on that physical size; everything will be the same size, but twice as crisp.

Update: This is what System76 does on its larger-display laptops like Oryx Pro and Bonobo WS: the standard display is 1920×1080, while the HiDPI display is 3840×2160.

However, on a smaller display like 12 or 13”, 1080p at 1× is far too dense (meaning the UI is far too small) for most users. So 4K on this physical size is actually worse than something like 3200×1800 (equivalent to 1600×900 pixel doubled).

Update: This is why the System76 Galago Pro has a 13” HiDPI display at 3200×1800. When running in LoDPI mode (i.e. connected to a LoDPI external display), it runs at 1600×900 to maintain the exact same physical size.

Oftentimes people ask if elementary OS will support non-integer scaling to cater to users of products with these poor size/resolution combinations. But since half pixels are a lie, it’s not something we’re going to go out of our way to do. The manufacturer made a poor decision and sold a bad product. There’s not much we can do to fix that.

Update: Underlying GNOME technology is working on fractional scaling support when running under Wayland. Once elementary OS is using Wayland, we may support fractional scaling as a non-default hardware workaround. But we plan to always stick to real pixels by default.

The Takeaway

- HiDPI ideally means pixel-doubling

- Half pixels are a lie

- 4K does not mean HiDPI, and might not always be the best resolution

- Some manufacturers make poor decisions

Let me know if this helped you out or if you have your own thoughts; tweet at me or comment here. :)

Thank You

Thanks to all of our supporters, backers, and customers! Your contributions make elementary possible. If you’d like to help build and improve elementary OS, don’t hesitate to Get Involved.

We’re accepting limited sponsors for the elementary Blog. View our public analytics and learn more if you are interested.